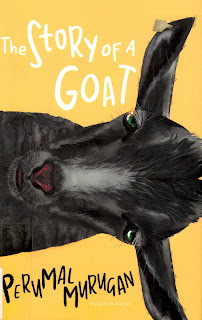

Perumal Murugan, The Story of a Goat (Londres: Pushkin Press, 2018 [2016]). 183 pages. Translated from the Tamil by N. Kalyan Raman.

“The birth of an ordinary creature never leaves a trace,

does it?” Well, it does, actually: for an old couple of the farming poor in

India who have survived in a small, arid village in the south, the arrival of a

puny black baby goat becomes an unforgettable event.

They name the kid Poonachi, and the ginormous man who leaves

the goat behind in their care assures them Poonachi, a female, is truly a

miracle. Despite their scarce resources, the old couple take the creature in

and do their best to feed her.

The country depicted by Murugan has a government that is incredibly

inquisitive about what animals people have. Strict controls take place and

tough questions are asked if the animal’s provenance cannot be ascertained. At

home, Poonachi is ostracised by most other goats and cannot feed on the

nanny-goat’s milk. The old woman, however, ensures the little black goat will

grow.

Murugan writes about the life of a goat while deftly

constructing a more than entertaining allegory for the human condition. Through

Poonachi’s story and point of view, we are ‘treated’ to the many misadventures,

cruelties and sad events that mark a female animal’s life in a poor area. While

Murugan is apparently focusing us on the hardships of people and the worries

and humiliation the absurdly strict rules of the government of the country can

inflict on the vulnerable, on another level the book works as a profoundly

bitter denunciation.

|

| Perumal Murugan: Another author to pay close attention to. Photograph by Augustus Binu. |

Poonachi’s survival as a baby goat just serves her on a

plate for more brutality and disappointment: Murugan’s narrative includes

scenes of castration, rape, erotic love and then frustrated romance. More than

a sad fable, The Story of a Goat comes across as a seriously inventive

reflection on existence, injustice and the human ability to withstand

misfortune. Murugan subtly warns the reader against complacency in a world

where ultraright-wing tumult and violence against women seem to go hand in hand.

N. Kalyan Raman’s translation occasionally sounds brilliantly foreign yet neat.

A nice little surprise of a book!